Aspects of Hunger ~Challenges for the Post-SDGs~

Recently, when I attended the World Energy Conference in the Netherlands in May, an interesting remark caused controversy.

“If we don’t eat food in the future, the world will be saved.”

This statement was made because of the enormous amount of energy used to produce food, but what does this phrase imply for the future food system?

First of all, I would like to define “hunger” in this paper. Although it is often confused with “poverty,” “poverty” itself generally refers to a state in which people do not have access to the goods and capital necessary for living due to their distance from society. On the other hand, “starvation” refers to a condition in which a person does not eat enough for a long period of time, becomes undernourished, and has difficulty in survival and social life. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines nutritional deficiencies as “the continuous inability to eat enough food, i.e., sufficient food energy to lead a healthy and active life.”

As stated in the second goal of the SDGs, while various NGOs and other non-governmental organizations are working to eradicate hunger, it has been pointed out that “about 800 million people are suffering from hunger while the world’s population exceeds 7 billion.” When we see this kind of “hype,” the majority of people think of the food supply and feel that it is better to increase the supply. Here, I would like to introduce two representative arguments regarding the eradication of hunger.

First of all, a typical argument would be that since the population is growing, it would be better to increase the food supply. The origins of this argument can be traced back to Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations.” In his Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that population growth is necessary for national wealth to increase, and that the development of a market economy will lead to the spread of wealth to the lower classes and the elimination of poverty [John, 24].

On the other hand, the British economist Thomas Robert Malthus later advocated that such population growth would have a negative impact on the food supply and demand system. In his famous book “The Theory of Population”, Malthus argued that the poor do not become rich even if the market develops, and attempted to disprove that population growth causes poverty [Jacopo, 24].

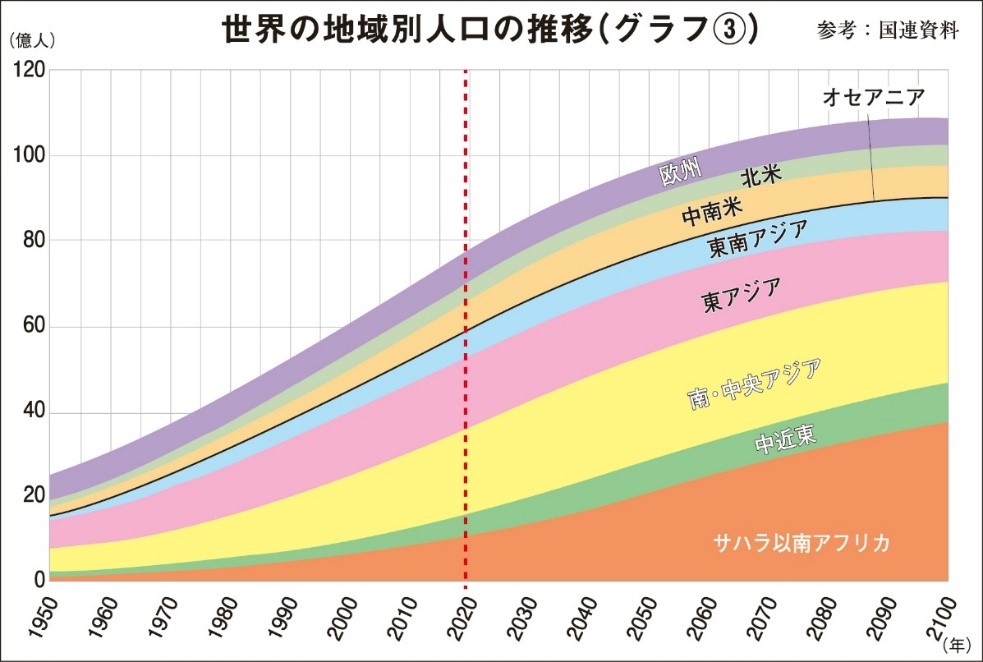

< Chart: Trends in Population by Region of the World>

(Reference: Our World in Data)

It is called the “Malthusian trap”, but Malthus’s opinion was in the minority when he advocated that the speed of population growth exceeded the amount of food supply, and that it was the era of the Industrial Revolution at the time. However, especially in view of the explosive population growth in emerging countries such as China and India, as well as the population of the African region, it can be said that Malthus’s claim has been inherited even in modern times. Is it really the collapse of the food supply and demand system due to population growth that is causing “hunger”? I would like to see the actual amount of food supply per capita in the world.

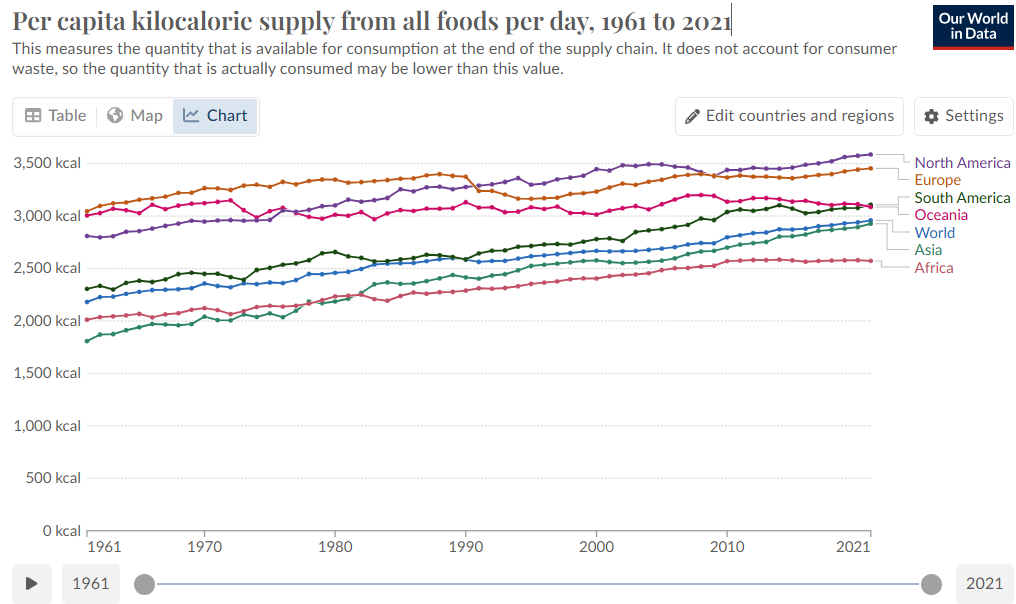

< figure: Food supply per capita>

(Reference: Our World in Data)

Looking at the amount of food supply since 1961, it is difficult to say that the supply itself has decreased, and the supply itself has not decreased in the African region. It is true that the pandemic of the new coronavirus and the war in Ukraine have caused supply chain restructuring and soaring prices of fertilizers, but it is still too early to conclude that supply is the cause of “hunger” itself. Rather, it is one of the proofs that we have been able to rebuild the food system even in the midst of multiple crises.

So where is the real problem? This demographic argument was challenged by Indian economist Amartya Sen. Sen points out that one of the causes of “hunger” is the relationship of title (related to legitimate rights based on social rules, such as the access, exchange, or use of food) [Bodo, 23]. In other words, famine does not occur because of a shortage of food supply, but because of the loss of the ability and right to obtain food. Certainly, if we go back to historical examples, Sen’s argument can be said to be valid as an explanation. For example, the Great Bengal Famine was a famine that occurred in Bengal, which is part of the British Indian Empire, in 1943, and as a result of the government’s food subsidies to certain people, food prices rose and many workers became extremely impoverished, leading to a “famine”. The government’s view at the time was that the famine was mainly caused by flooding caused by cyclones and reduced crop yields due to the development of mold diseases, so Sen used data to disprove it.

Sen’s argument leads to a debate about whether food supply and demand should be left to the market or whether government intervention is necessary. It is a naïve view that a certain amount of policy intervention is necessary in the modern food supply and demand system. If this is to be said on the premise of criticism, I think it is necessary to discuss the next post-SDGs with a view to reducing the amount of food supply.

< figure: Demonstrations in front of the European Union (EU)>

(Reference: Hungary Today)

Finally, I will discuss the points that need to be discussed in order to solve the problem of “hunger” in the future. The first is whether the food system should be left to the market. Tracing the historical lineage so far, we have touched on the risk that population growth has had a certain degree of impact, and on the other hand, if left to policy, the natural balance of supply and demand will be ubiquitous in Japan and overseas, causing “starvation.” It is true that if you leave it to the market, the market will be unevenly distributed where there is a lot of demand. This phenomenon is called “hunger during economic boom,” and it is quite possible that food exports to other countries will increase while the domestic hunger problem is occurring. In the future, it will be necessary to control these market forces to a certain extent.

The next thing to consider is food production targets. At first glance, the logic of eliminating “hunger” by increasing the target production of food sounds convincing, and such support is mainstream in Japan as well. On the other hand, if we really increase production, will we be able to eliminate hunger, which is one of our global goals? For example, in the midst of what can be called an energy crisis, the implementation of food production will require more energy for production, and the squeeze will affect farmers. In fact, in Brussels, where the EU is at its feet, farmers who are struggling to produce have gathered under ambitious environmental and energy policies, blocking roads and causing large-scale demonstrations.

Reducing food loss and loss is important, but it is also important to take a policy approach to maintain the current food supply and demand system. Otherwise, if we raise food production targets too easily, the ripples may spread globally, and as a result, “hunger” itself may spread rather than eradicate it. In order to engage in such multifaceted discussions toward the next SDGs, it is necessary for humanity to consider how to deal with “hunger” in the post-SDGs era.

Corporate Planning Group Shugo Iwasaki

(References)

[Bodo, 23] Herzog, Bodo. “Review of: Economics rationality in the world of Amartya Sen.”

[Jacopo, 24] Bonasera, Jacopo. “The opacity of a system TR Malthus and the population in principle.” History of European Ideas: 1-15.

[John, 24] Robertson, John. “The legacy of Adam Smith: government and economic development in the Wealth of Nations 1.” Victorian Liberalism. Routledge, 2024. 15-41.